I'm not an expert—on climate change or, let's be honest, anything—but I do have a compulsive (and rather self-destructive) tendency to marinate my brain in a potent parlay of doomsday pornography and environmentalist tears. The consequence of this endeavor is that over the years the once viable gray matter that filled my dome has been reduced to a mason jar of mushy overnight oats. In fact, this obsession of mine at one point got so bad that I spent a full biblical sabbatical and any semblance of an inheritance from my grandparents pursuing a degree in Environmental Science. Part-way through I realized that collecting ice cores in Antarctica wasn't the most viable way to make rent as a tropical Jew, so I ultimately settled for the next best thing: an AgSci degree. If only my peasant ancestors from the Pale could see me now! "Oy vey, what a shvindl," they'd say, before promptly wiping their ass with it and throwing it in the compost bin.

Regardless, this obsession of mine has somehow afforded me a position of unwarranted authority amongst my more credulous of peers. More and more—like a geriatric Costco employee manning my station—the wailing of hungry minds beckons for the deliverance of my slop. It is in service of this noble pursuit that I dedicate myself to forever wander the bulk aisles of knowledge, hairnet in full force, gloves deep in the trough of despair, dixie cups aplenty, just to sling bite-sized truths out to you. Here I am world. Free samples!

Satiate the masses for long enough and you start to pick up on some best sellers. So today, valued customers, I have by popular request the following tray of knowledge out on display:

Hey Ber, what's the best way to lower my carbon footprint?

When most people tackle this question, they tend to zero in on a handful of usual suspects: airfare, diet, electrification, and so on. Meanwhile, at the other end of the spectrum, some prefer a more nihilistic approach. They choose instead to punt such personal obligations to the bloated billionaire class, whose emissions dwarf our own into perceived insignificance. Lost sailors marooned on the fiberoptic seas sing their usual shanties: "There is no ethical consumption under capitalism," they belt as the Siren known as Temu seduces them against the rocks. Both positions, while seemingly opposed, share a common ancestor: manufactured consent. Or as it's known to those who refuse to scan a QR code at a restaurant: "the system's neatest trick." These competing narratives actually serve to accomplish the same goal: the quiet surrender of agency to a system designed to pacify our capacity for intrinsic change.

Both schools of thought are a clever—and deeply insidious—byproduct of commercialism. One path achieves complacency through constructing a paper tiger. In elevating the all-powerful billionaire class to that of demigod status, the pessimist becomes neutered. The ego lobotomized.

Meanwhile, a network of electro-mechanical relays meticulously virtue-signals the optimist into falsely conflating their purchasing power with real forms of resistance. In both scenarios the results are identical: self-worth is flattened into little more than a blip on a quarterly earnings report. This trips the propaganda immune system, causing a potent inferiority complex so feverish that it spawns a regressive metamorphosis.

The individual, once-brimming with confidence in its own capacity for the enactment of change, is now fully domesticated from both ends. As the soul begins its gradual decline toward the economic role of a docile bottom feeder, something ugly begins to take shape. The drowning specimin finds their once-extended fist loosened in search of a palm to latch onto. No longer able to recognize itself among others in a sea of marooned prayer, whatever remaining portion of one's self that craves a more equitable world now drifts further and further from the shore. Fully encased in a chrysalis of anger, skepticism, and despair, the symptoms of discontent manifest so potently in the subconscious that—faced with a watery grave—the mind latches itself on to any raft that offers ideological reprieve.

Now aboard its very own algorithmic lifeboat, the newly minted Kafka-esque consumeroid begins—for the very first time—to burrow its still shrink-wrapped feeding tubes into the mass-produced supply of deliverance that awaits along every digital shore. Making its way inland through the information inlets of our self-appointed Anthropocene—waters oozing with the chemical byproducts of labububs and last year's iPhones—a factory of outrage machines sits, humming out distractions with astonishing harmony to perpetually obscure oneself from ever accidentally consuming anything of nutrition, all so that the meat market never exhausts its supply of undivided attention.

Speaking of which, it is within the final stages of this transmutation that a parasitic force—"the media"—takes its hold as well. The mind—now larval in its capacity—becomes encased in an echo-chamber void of nuance. Its cocoon form is then unrelentingly pumped with a toxic cocktail of sepsis-inducing noise that stimulates the victim's glands into spinning legal tender like silk. Wings are clipped. Colorful pigments fade. The transformation, both brutal and swift, now complete.

The self, once fully reduced to a larval state, craves but one thing: more.

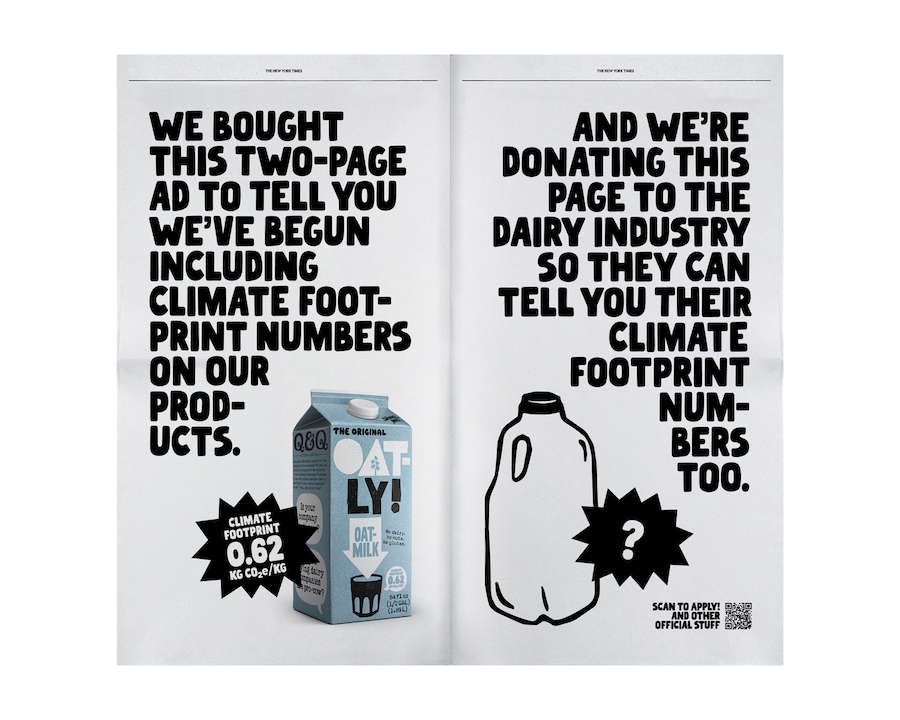

And thus, consumerism has fully achieved its original goal. A new market emerges to quench humanity's insatiable thirst for morality in the 21st century. The very apparatus responsible for entrenching us in the climate crisis—industrialization—now sells us salvation from it wholesale. Better yet, this deliverance leverages all the free market's finest innovations. Relief through commodification takes care never to assume permanent form. Change is sold iteratively through painstakingly slow, inconsequential reforms. Packaged with planned obsolescence, tiered piety, and the relentless churn of both fashion and fad, greater salvation always lies just beyond the horizon.

Once more, the media takes center stage. Its natural habitat ravaged by 21st century exploits, the once respected keystone species known as the Journalist has been reduced to serving the cause of consumption by proxy. Its bread now buttered by the apex predators atop the economic food chain; the fourth estate latches its venomous teeth into its former benefactor. A continuous supply of manufactured outrage is pedaled in bulk, drawing unsuspecting victims towards their own harvest like moths to the flame. A once well-respected institution, journalism today has been reduced to that of a Pulitzer marketing department; Woodward and Bernstein watch on in horror as today's deep throats are silenced by a viscous coating of whatever alternative milk dominates the current fad. Best of all, once an industry has been sufficiently greenwashed by this process, another instantly ripens. Thus, the domestication of the activist—from wild creature to livestock—is now fully complete. The ideal consumer assumes its final form: a legless, pacified grub, forever suckling at the teat of the industrial beast it long ago conjured.

The problem with commodifying and budgeting one's emissions into a portfolio of neatly bundled lifestyle choices is that it omits several key variables—uncomfortable ones—which collapse the carbon-footprint narrative entirely. But before we delve too deep, let's revisit the basics:

The carbon cycle is the natural process by which carbon moves through Earth's atmosphere, biosphere, hydrosphere, and geosphere. Carbon exists in various forms, including carbon dioxide (CO₂), methane (CH₄), carbonates, and organic matter. Some forces emit carbon, while others sequester it.

When you hear the term "carbon neutral", this means a product or service has balanced its total CO₂ emissions with supplementary CO₂ removal (e.g., reforestation, carbon capture). This is different from "net zero", which refers to balancing all greenhouse gases (CO₂, methane, nitrous oxide, etc.).

When we talk about achieving both carbon neutrality and net zero, we're referring to an annual balance between emissions and removals. This does not, however, account for the cumulative deficit built up since the Industrial Revolution.

Think of it like this: if you've been maxing out your credit cards for 200 years, simply paying the minimum monthly balance doesn't mean you're debt-free. You're just not digging the hole deeper—for now.

Net zero is a break-even point on the path to what's sometimes called "net-negative emissions"—a hypothetical state where more CO₂ is removed than emitted, eventually (hopefully) restoring pre-industrial CO₂ levels (≈280 ppm).

To "equitably" achieve such a feat, emissions are often conceptualized via what is colloquially referred to as a "carbon footprint."

A carbon footprint simply refers to a rough measurement of one's own direct share of net global emisisons. Carbon footprints, by the way, follow a rigid hierarchy. Some consumeroids are much juicier than others.

| Country | Per-Capita Emissions | Population |

|---|---|---|

| Qatar | 37.6 Tons | 2.68 Million |

| United Arab Emirates | 25.8 Tons | 9.36 Million |

| Bahrain | 25.7 Tons | 1.46 Million |

| United States | 14.9 Tons | 332 Million |

| Libya | 9.2 Tons | 6.73 Million |

| China | 8.0 Tons | 1.41 Billion |

| South Africa | 6.7 Tons | 59.39 Million |

| Suriname | 5.8 Tons | 612,985 |

| Chile | 4.3 Tons | 19.49 Million |

| Argentina | 4.2 Tons | 45.81 Million |

| Brazil | 2.2 Tons | 214.3 Million |

| Peru | 1.8 Tons | 33.72 Million |

| Paraguay | 1.3 Tons | 6.70 Million |

| Nigeria | 0.6 Tons | 213.40 Million |

| Sudan | 0.5 Tons | 45.66 Million |

| Ethiopia | 0.2 Tons | 120.3 Million |

| Somalia | 0 Tons | 17.07 Million |

| DR Congo | 0 Tons | 95.89 Million |

| CA Republic | 0 Tons | 5.45 Million |

| Additional Context: Despite having a combined population that equals that of the United States, Nigeria and Ethiopia together emit CO2 at rates that are 24.8 to 74.5 times lower per capita. |

The table above tells of a timeless tale.

Of course, the public is never given a concrete number to strive for in terms of personal reductions. Industry always prefers to under-promise and over-deliver. Instead, the system errs on the side of caution through abstractly encouraging individuals to reduce this figure as much as possible in order to assist in balancing the whole. This also has the convenient side-effect of always leaving consumers seeking more—the perfect recipe for perpetual consumption.

That being said, it's actually dumbfoundingly simple to quantify this ideal figure. However, doing such reveals the fundamental flaw in the entire carbon footprint narrative—it treats the symptom while ignoring the disease.

Ideal Footprint = total sequestration / global population

Or, for those who prefer their math with a side of existential dread:

Your Fair Share = (Earth's ability to clean up our mess) ÷ (number of humans making said mess)

In other words, to achieve net-zero one's ideal footprint should represent an equal share of the planet's total sequestration budget. But this simple equation reveals something far more profound than mere carbon math: it exposes the fundamental contradiction at the heart of our consumer society.

The carbon footprint narrative isn't just incomplete—it's a distraction from the real problem: we're treating the smoke while the house burns down. Carbon emissions are merely the byproduct of our real problems: overshoot, environmental degradation, and natural resource depletion.

Consider the variables hidden in plain sight: the sequestration budget isn't fixed—it's shrinking as deforestation, ocean acidification, and soil degradation chip away at Earth's ability to clean up our mess. Meanwhile, our population continues to grow, meaning we're dividing a shrinking pie among more and more people.

And here's the ultimate irony: climate change creates conditions that require more energy consumption to survive. Air conditioning becomes necessary where it wasn't before. Desalination plants become essential as freshwater sources dry up. It's like trying to bail out a sinking ship while someone keeps drilling more holes in the hull.

But the most insidious variable is the one the carbon footprint narrative conveniently ignores: most of your emissions actually come from your bank account, not your lifestyle. That retirement fund invested in fossil fuels? That checking account financing deforestation? That 401(k) underwriting industrial agriculture? These emissions dwarf your personal consumption, but they're neatly excluded because they're "someone else's problem."

Every ton of CO₂ emitted represents resources extracted from the Earth: minerals mined, forests cleared, soils depleted. Modern agriculture doesn't just emit carbon—it destroys topsoil, pollutes waterways, and decimates biodiversity. The carbon footprint of your almond milk conveniently ignores the water crisis in California or the soil degradation that makes such industrial agriculture possible.

So where does this leave us? Staring into the abyss of our own making, armed with nothing but a calculator and the sinking realization that we've been sold a bill of goods.

The carbon footprint narrative isn't just incomplete—it's actively harmful. It individualizes a systemic problem, commodifies our anxiety, and distracts us from the real issues. It turns environmentalism into another consumer product, complete with planned obsolescence and tiered subscription plans for your conscience.

But here's where the real metamorphosis begins—not as consumers trying to optimize our footprint, but as humans reclaiming our agency. The path forward isn't through better shopping choices—it's through better living choices. It's about reconnecting with the land, with our communities, and with ourselves. Imagine this re-metamorphosis: the legless larva, once pacified at the industrial teat, begins to remember its wings. The chrysalis of despair cracks open not to reveal another consumer, but something ancient and wild—a creature that knows how to build rather than buy, to mend rather than replace, to grow rather than consume. A being that understands that true abundance comes not from having more, but from needing less.

This re-metamorphosis beyond consumerism means embracing our agrarian roots, focusing on localized systems, supporting one another neighbor by neighbor, and rejecting the endless cycles of consumption. It means recognizing that the solution to consumerism isn't different consumption—it's less consumption.

We cannot control the coming correction, but we can prepare ourselves to be the best versions of ourselves should we be fortunate enough to make it to the other side. This means building resilient communities, priming ecosystems for regeneration instead of destruction, and creating nested systems that work with nature rather than against it.

So the next time someone asks you about your carbon footprint, tell them you're working on something more important: your ecological handprint. Because while footprints measure what we take, handprints measure what we give back.

And if that doesn't work, just tell them you're boycotting carbon math until they fix the underlying assumptions. Some things are worth making a scene about—even in the Costco sample aisle.

After all, the house always wins when you're playing their game. The real victory comes when you stop playing altogether and start building your own.

Pin a Comment