I find sodomy to be a tremendous pain in the ass. That is, the term not necessarily the act. It is written in the Hebrew bible -and thus plagarized in many others- that "Sodomy" refers to the story of Sodom (Genesis 19), where the sin of the city was traditionally interpreted as inhospitality, greed, and both sexual and non-sexual violence. Early Jewish and Christian commentary clearly emphasized the broader moral corruption of Sodom rather than hyper-fixating on the same-sex behavior that occured in the climax of the story.

In fact, it was not until Medieval & Later Christian Interpretation that the term became increasingly associated with non-procreative sexual acts, especially anal sex (whether same-sex or heterosexual). Over time, it narrowed further to primarily denote male homosexual acts due to cultural and legal stigmatization. Today, "sodomy" is almost exclusively conflated with anal sex between men, and in legal contexts, it has been used to criminalize homosexuality.

This is a classic example of manufactured pejoration. Where standard pejoration describes the natural drift of a word's meaning toward the negative, the manufactured variety is a deliberate, bad-faith redefinition engineered to serve an agenda—in this case, sexual repression. It is, in effect, "definitional gerrymandering"—or, to put it more bluntly, the outright weaponization of language.

This concept, of course, is far from new. George Orwell's seminal novel, 1984, examined this phenomenon with such clarity that it gave us the term "Orwellian" to describe manipulative and deceptive language. The ultimate irony is that Orwell himself became an example of this metamorphosis, as his name was redefined to represent the very tool of propaganda he warned the world against.

Which brings me to the subject of today's post: Zionism. A word which -amongst goyim- has reached a level of cognative dissonence and coloquial hysteria so potent that its meaning has splintered into little more than an opaque slur.

The definition of Zionism is and always has been a simple one, best understood through the following photos:

To understand the birth of modern Zionism, we must situate it in its historical moment. The late 19th century was an era of surging nationalism across Europe—Italians, Germans, Poles, and countless other peoples were forging nation-states from ancient identities. Theodor Herzl, a Viennese journalist covering the Dreyfus Affair in France, witnessed firsthand how even in the most "enlightened" of European societies, antisemitism could erupt with shocking ferocity. His 1896 pamphlet "Der Judenstaat" ("The Jewish State") articulated what many Jews across the diaspora already felt: that no matter how assimilated they became, they would always be seen as outsiders in European societies.

Herzl's vision was fundamentally liberal and pragmatic. He imagined a modern, democratic Jewish state that would normalize Jewish existence and provide safety through sovereignty. Early Zionist thinkers like Ahad Ha'am emphasized cultural renaissance alongside political sovereignty, while socialist Zionists like Ber Borochov (nice) envisioned Jewish national liberation as part of a broader class struggle. The movement was diverse, but united by the recognition that Jewish safety could no longer depend on the goodwill of host nations.

Like all nationalist movements of the era, Zionism contained its share of hardliners. Revisionist Zionists led by Ze'ev Jabotinsky argued for more assertive territorial claims and military preparedness, believing that only "iron walls" could secure Jewish survival. Their positions, while controversial, must be understood in the context of Jewish powerlessness during centuries of pogroms and persecution. When your people have been repeatedly slaughtered while the world watches, the desire for self-defense becomes not just strategic but existential.

Simply put: After millennia of persecution with no viable refuge, the Jewish people—armed with roughly 4,000 years of firsthand experience overcoming competitive antisemitism—decided enough was enough. The only path to salvation was through self-determination. Preferably in their ancestral homeland—the one place on Earth with profound historical and religious significance to all Jewish identity—a land which, contrary to popular belief, has maintained a continuous Jewish presence in some form for millennia, despite unimaginable persecution from empire to empire.

Still, what's often forgotten in contemporary debates around Zionism is what happened after Herzl:

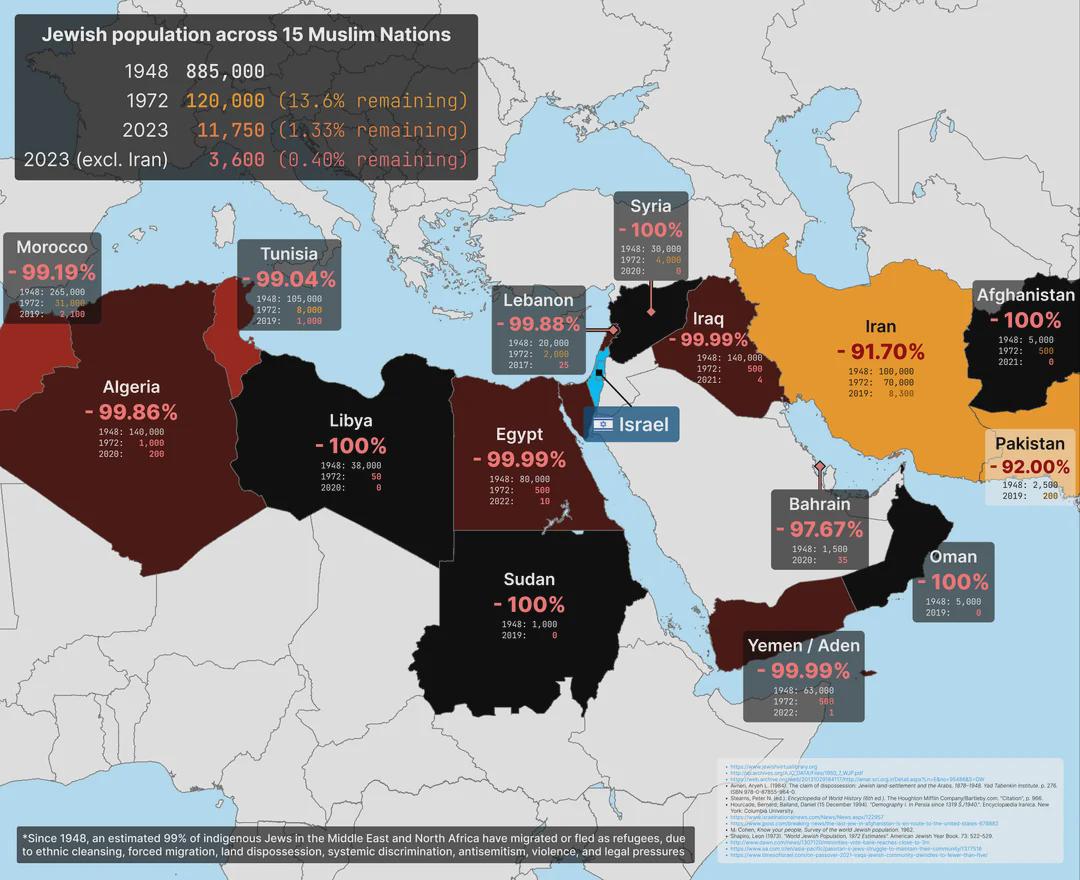

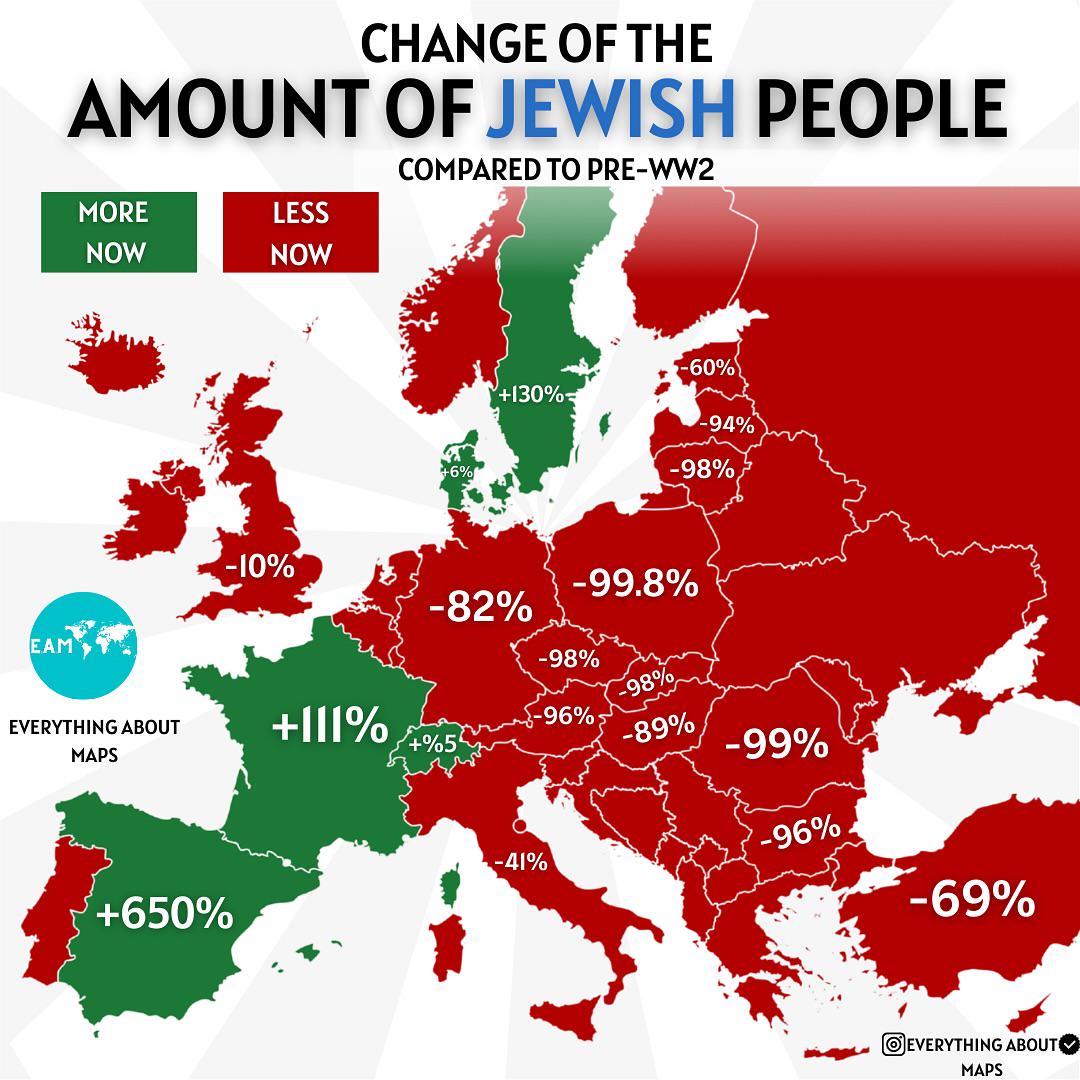

The extermination of 6 million Jews across Europe in WWII; the mass exodus of Jewish communities from the Middle East and North Africa between 1948 and 1972; the persecution and displacement of ancient Jewish communities in Iran and across the Soviet Union; the plight of Ethiopian Jews facing famine and civil war; and more.

This history reveals a crucial truth often obscured by opponents of Zionism who frequently rely on slogans such as "white settler-colonialism" or "ethno-nationalism" to discredit Israel: Jewish identity is astonishingly diverse. The common perception of Jews as uniformly "white" or European ignores the rich tapestry of Jewish ethnicities that span the globe. Understanding this diversity is essential to understanding Zionism itself.

The Jewish world is traditionally divided into three major ethnic groups: Ashkenazi Jews from Central and Eastern Europe; Sephardi Jews from Spain, Portugal, and the Mediterranean; and Mizrahi Jews from the Middle East and North Africa. Each group developed distinct cultural traditions, religious rituals, languages, and even culinary specialties while maintaining the core tenets of Jewish faith and law.

Beyond these major groupings, Jewish diversity extends even further: Beta Israel Jews from Ethiopia, Bene Israel from India, Bukharan Jews from Central Asia, and countless other communities have maintained Jewish identity for centuries in diaspora. When Zionism speaks of Jewish self-determination, it speaks for this entire spectrum—not just the European Jews who dominate Western media representations.

This skewed perception didn't emerge by accident. The history of Jewish immigration to the United States—the primary lens through which many Westerners view Jewish identity—was disproportionately comprised of white-passing Ashkenazi Jews. This was due to the fact that they were, relatively speaking, seen as closer to the white American melting pot ideal that many institutions upheld in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. While Ashkenazi Jews still faced significant antisemitism and discrimination, their European origins made them more assimilable in the eyes of American immigration authorities and society at large compared to their Sephardi and Mizrahi counterparts.

The result is what we might call a "demographic sampling bias" in the American Jewish experience. Because the largest waves of Jewish immigration to the US came from Eastern Europe between 1880-1924, American Jewish identity became largely synonymous with Ashkenazi identity in the popular imagination. This created a feedback loop where American media, politics, and culture reinforced the image of Jews as white Europeans, effectively erasing the majority of world Jewry from public consciousness.

This myopia has manifested devastating consequences for global Jewry today. But not before first revealing the full extent of American apathy towards its predominantly Ashkenazi Jewish citizens and their brethren abroad during one of the darkest chapters of Jewish history to date. As the Nazi genocide unfolded across Europe, the United States shamefully closed its doors to Jewish refugees—especially those who were not white. Despite knowing of the systemic extermination occurring in concentration camps, American immigration policies remained restrictive, with officials actively turning away ships like the MS St. Louis in 1939, forcing 937 Jewish refugees to return to Europe where many would perish in the Holocaust. This callous indifference continued even after the war's end, as the US maintained strict immigration quotas that prevented Holocaust survivors from finding refuge. These events, paired with rising antisemitism domestically from figures which have stained American history such as Charles Lindbergh, Henry Ford, and even the rise of the "American Nazi Party" alongside that of German Nazism, profoundly impacted not only the Zionist movement globally but right in the heart of America.

The tragedy of Jewish displacement also didn't end with the liberation of the camps. In countries like Poland—which had been ravaged by Nazi occupation—many citizens maintained deep-seated antisemitic sentiments. Rather than recognizing Jews as fellow victims of Nazi brutality, some Poles blamed their Jewish neighbors for the destruction and carnage they had endured. This poisonous scapegoating culminated in horrific pogroms like the 1946 Kielce massacre, where 42 Holocaust survivors were murdered by a Polish mob just one year after the war's end. State-sanctioned attacks against Jewish communities continued across Eastern Europe, demonstrating that even the revelation of the Shoah's horrors couldn't extinguish ancient prejudices.

For Jews worldwide, these events cemented beyond any doubt the necessity of a sovereign nation that could protect Jewish lives. The Holocaust had demonstrated that even "enlightened" Western nations would turn their backs on Jewish suffering, while post-war pogroms proved that ancient hatreds survived even the most horrific genocide. Zionism was no longer merely a political ideology or cultural aspiration—it had become a matter of existential survival. The Jewish people needed a homeland not just for self-determination, but as a refuge—a place where Jews of all backgrounds could find safety when the world once again closed its doors.

The founding of Israel in 1948 brought salvation for many Jews around the world, but also tragically endangered others by shining a spotlight on them. When Israel declared independence, all of its Arab neighbors immediately declared war, vowing to destroy the newly formed Jewish state. This conflict created a complex humanitarian tragedy that continues to shape the region today.

The Nakba—Arabic for "catastrophe"—refers to the displacement of approximately 700,000 Palestinians during the 1948 war. This was indeed a tragic human suffering that should not be minimized. The right to return for these Palestinians is a subject of modern discourse still, and one which I can personally greatly empathise with. Further complicating this historical event is something which many outside of Israel/Palestine do not know: many Palestinians chose to remain in their homes despite this conflict. These Palestinians would go on to receive Israeli citizenship, study in Israeli universities, maintain their own communities, sit in government, serve as judges, and even as Supreme Court justices who have charged sitting prime ministers with corruption. Today they make up roughly 20% of Israel's population as full citizens with equal rights under law.

Yet despite these successes, deep scars remain from this historical division. While many Arab Israelis are proponents of the state today, the events of 1948 divided families and communities in ways that still profoundly persist. Many have relatives living in a diaspora they cannot reunite with. And while some Arab citizens proudly identify as Israeli—with many even volunteering for the IDF (which is compulsory for Jews but not Arabs)—others embrace Palestinian identity for the same reason the Jewish state was founded: self-determination. The wounds of this period remain fresh, history is still being written, and today more than ever, compassion and understanding are worth more than gold.

What's often further missing from discussions of the Nakba is the parallel tragedy that befell Jewish communities across the Arab world. As Israel fought for its survival, ancient Jewish communities that had existed for millennia in countries like Iraq, Yemen, Egypt, Syria, and Morocco suddenly found themselves targeted. Jews who had lived alongside Muslim neighbors for generations were now seen as fifth columnists—collectively blamed for the actions of a distant state they had no connection to. Much like Japanese-Americans during WWII or other groups throughout history, they became scapegoats for geopolitical conflicts they had no part in creating.

The result was a systematic campaign of persecution that mirrored the European antisemitism Jews thought they had escaped. Jewish homes and businesses were looted and burned. Synagogues were desecrated. Thousands were killed in pogroms, like the 1941 Farhud in Iraq where 180 Jews were murdered. Jewish populations that had numbered in the hundreds of thousands were systematically stripped of their property, their citizenship, and their dignity. Ultimately, nearly 900,000 Jews were forced to flee Arab countries, arriving in Israel with nothing but the clothes on their backs.

These Mizrahi and Sephardi refugees now constitute the majority of Israel's Jewish population. Their story represents one of the largest and most overlooked refugee crises of the 20th century—a population exchange that saw nearly equal numbers of Palestinians and Jews displaced. Yet while the Palestinian refugee crisis remains central to international discourse, the Jewish exodus from Arab lands has been largely forgotten, creating an imbalanced historical narrative that obscures the full complexity of the conflict.

What emerges from this history is a fundamental truth: Israel today is a nation comprised of survivors. It is a refuge built by refugees from all over the world who had nowhere else to go. From Holocaust survivors who lost everything in Europe, to Mizrahi Jews expelled from Arab lands, to Ethiopian Jews airlifted from famine and civil war, to Soviet Jews fleeing renewed antisemitism after the USSR's collapse—Israel represents the last sanctuary for Jewish people when the world closes its doors.

There exists a persistent misconception that many Israelis are "dual nationals" who can simply flee whenever conflict breaks out. This is not even remotely true. Less than 10% of Israelis have dual citizenship, and many of these hold dual nationality in name only. They are in practice prohibited from returning to their ancestral homes in countries like Iraq, Yemen, Syria, and Egypt by deliberate policies that continue to this day.

Finally, I want to expand upon one more thing: everything I have discussed here barely begins to scratch the surface of both Zionism and Palestinian self-determination. The conflict in Gaza we are witnessing today, the infinite complexities of the broader geopolitical region, the religious and cultural differences that shape such communities, the unhealed wounds—all of this brings us to the heart of the matter. The Israel/Palestine conflict is a reflection of the much larger human condition. How do we, as people, bridge religious differences? How do we squash extremism? How do we forgive and move past cycles of violence? This, in my opinion, begins with understanding that Zionism is not incompatible with Palestinian nationalism. They mirror one another, and prove one another's necessity.

Both movements encompass diverse views and perspectives that platforms like TikTok and Twitter could never fairly portray. Both represent peoples who have known displacement, persecution, and the yearning for self-determination in their ancestral homeland. The tragedy is not that these two national aspirations exist, but that they have been pitted against each other in a zero-sum framework that serves neither people's long-term interests. The path forward requires recognizing that Jewish and Palestinian national identities are not mutually exclusive, but rather interconnected parts of the same regional tapestry.

Just as Zionism in its purest form represents the culmination of Jewish survival against unimaginable odds, Palestinian nationalism at its finest is the legitimate aspiration of a people seeking dignity and sovereignty. The challenge—and the opportunity—lies in building a future where both can coexist in peace and security without being hijacked by those who cowardly and zealously insist upon the destruction of one another.

To recap, Zionism is NOT:

- White: Jewish identity spans the globe with Ashkenazi, Sephardi, Mizrahi, Beta Israel, and countless other communities. The perception of Jews as uniformly "white" stems from demographic sampling bias in Western immigration patterns, not historical reality.

- Colonialism: Zionism represents the return of an indigenous people to their historic homeland, not the imposition of foreign rule. Unlike classic colonialism that extracts wealth for distant empires, Jews returned to rebuild their own society in the land where their language, culture, and kingdom originated millennia ago.

- Racism: Zionism is about self-determination, not supremacy. Israel's Declaration of Independence guarantees equal rights for all citizens, a principle lived by its two million Arab citizens who serve in government, judiciary, and society. The true racism lies in the assumption that Jews cannot self-govern without becoming oppressors.

- Monolithic: Zionism encompasses diverse perspectives—from secular socialists to religious traditionalists, from two-state advocates to those with different visions. This ideological diversity reflects a living, breathing national movement, not a singular dogma.

- Opposition to Palestinian Rights: Zionism and Palestinian nationalism are not mutually exclusive. A significant strand of Zionist thought supports Palestinian statehood, recognizing both peoples' legitimate national aspirations. The false dichotomy that forces a choice between Jewish and Palestinian rights is the very tautological trap this essay describes.

- A License for War Crimes: This conflates policy with principle. Criticizing specific Israeli actions is legitimate, but weaponizing those criticisms to invalidate Jewish self-determination is a logical fallacy. Holding Israel to high standards is just; holding it to a solitary standard of flawless conduct that no other nation could meet is not scrutiny, but demonization.

This brings us full circle to where we began: the tautological redefinition that transforms Zionism from a movement of national liberation into a rhetorical bogeyman. We're left with a situation where saying "I'm a Zionist" is treated like saying "I enjoy kicking puppies"—a statement so morally repugnant that it requires no further explanation. The tautology has become self-sustaining: "Zionism is bad because it's Zionism."

This linguistic gerrymandering serves multiple agendas simultaneously. For antisemites, it provides a socially acceptable way to express ancient prejudices. For political activists, it creates a convenient bogeyman. And for the intellectually lazy, it offers pre-packaged moral certainty without the inconvenience of historical nuance.

The solution, as with all tautological traps, is to insist on precision. When someone says "Zionism," ask them to define their terms. Challenge the circular logic. Remind them of the histories we've examined—of Jewish diversity, of Mizrahi refugees, of the complex tapestry that makes this conflict so resistant to simple solutions.

Because if we allow language to be hijacked this way, we're not just losing definitions—we're losing the ability to think critically about complex issues. And when we lose the shared language to debate our differences, we destroy the very bridge that any lasting peace must be built upon.

Salam & Shalom,

-Ber

Pin a Comment